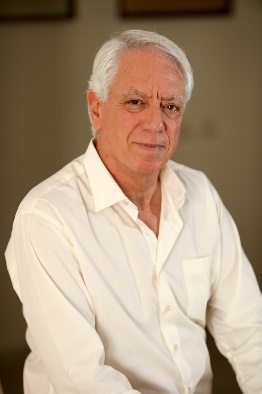

With the 2018 World Cup approaching, the journal Le Monde, 5 June 2018, featured the topic of how fear of ridicule explains most missed penalties, citing the research of Prof. Michael Bar-Eli and Prof. Ofer Azar from the Department of Business Administration of the Guilford Glazer Faculty of Business and Management GGFBM at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in the journal's online video report. This report's premise: In soccer, the penalty is one of the safest ways to score a goal. According to available data, about 75-80% of penalties turn into goals. However, Bar-Eli and Azar suggest that soccer players miss more than they should, and this could be because of the fear of ridicule. Kickers can miss fewer penalties if they practice shooting to the upper third of the goal, and in particular the top corners, where the goalkeeper has no chance to stop the ball. With proper practice, the kickers' chances to miss the goal should be quite low, improving their current 75-80% success rate. However, the current risk, that the goalkeeper stops the ball, becomes a risk of the ball going outside the goalframe when aiming to the upper third. Even though for the team it only matters to maximize the chances of scoring, the kicker may appear more ridiculous after missing the goalframe altogether than after having a penalty stopped by the goalkeeper. Therefore, the kickers prefer a lower chance of scoring by shooting low and allowing the goalkeeper a chance to stop the ball, instead of shooting to the corners to maximize scoring chances.

The research studies cited are:

Penalty kicks in soccer: an empirical analysis of shooting strategies and goalkeepers' preferences – Michael Bar-Eli, Ofer H. Azar

Action bias among elite soccer goalkeepers: The case of penalty kicks – Michael Bar-Eli, Ofer H. Azar, Ilana Ritov, Yael Keidar-Levin, Galit Schein

According to additional research of Bar-Eli and

Azar (with Ilana Ritov from the Hebrew University and two former students),

however, the goalkeepers also make mistakes in order not to appear foolish or

lazy. In the goalkeepers’ case, the mistake is to stay in the goal’s center

very rarely, whereas it turns out that this is actually where the chances to

stop the kick are highest, based on the actual distribution of penalty kicks

they collected from about 300 penalties. The explanation for this goalkeeper’s behavior

of almost always jumping, is that the norm is to jump, implying that a goal

scored yields worse feelings for the goalkeeper following inaction (staying in

the center) rather than following action (jumping), leading to a bias for

action. “The omission bias, a bias in favor of inaction, is reversed here

because the norm here is reversed – to act rather than to choose inaction. The

claim that jumping is the norm is supported by a second study, a survey

conducted with 32 top professional goalkeepers. The seemingly biased decision

making is particularly striking since the goalkeepers have huge incentives to

make correct decisions, and it is a decision they encounter frequently.” The

authors also discuss several implications of the action/omission bias for

economics and management. Their research on the action bias was cited in

numerous articles and was chosen by the New York Times as one of the important

ideas of the year, when it was published.