BGU Prof. Ehud Meron: "Instabilities are generally considered events to avoid, but in drylands they may prevent desertification"

Scientists at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev have shown in model studies that ecosystems may be rescued from collapsing to bare-soil, or desert states, by means of simple interventions at the desert border. "Deserts have been expanding for decades, but it doesn't have to be an irreversible process," says Prof. Ehud Meron of The Swiss Institute for Dryland Environmental and Energy Research (SIDEER), one of the Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research at BGU's Sede Boqer campus.

According to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, over 30 percent of the land in the United States is affected by desertification, which is defined as soil productivity loss and the thinning out of the vegetative cover because of human activities and climatic variations such as prolonged droughts and floods. Across the Atlantic, one fifth of Spain's land mass is at risk of turning into desert, while in China sand drifts and expanding deserts have claimed nearly 700,000 hectares of cultivated land, 2.35 million hectares of rangeland, 6.4 million hectares of forests, woodlands and shrub lands since the 1950s, according to the world body.

Meron's research group has developed a platform of mathematical models for dryland ecosystems that serves as an incubatory for novel ideas how to combat and even reverse the process of desertification. In a recent study that appeared in Physical Review Letters, postdoctoral fellow Dr. Cristian Fernandez-Oto (now at the University of the Andes, Chile), PhD student Omer Tzuk and Prof. Meron, used this platform to explored the possible role of instabilities in reversing desertification.

One form of desertification is a domino-like process of plant mortality at border lines between bare-soil and vegetation areas that results in a desertification front and the gradual replacement of vegetation by bare soil.

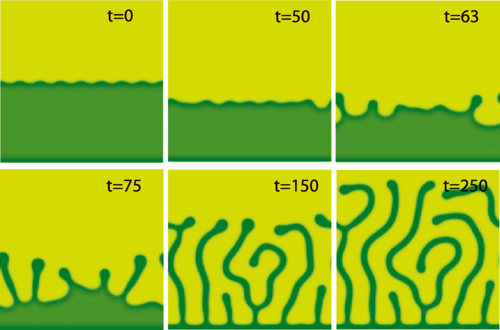

"We uncovered an instability by which straight desertification fronts develop vegetation fingers that grow backward into bare soil areas and thereby reverse the desertification process", says Prof. Meron. "The instability is realized under conditions of fast water transport towards the growing vegetation finger. Such water transport not only accelerates the finger's growth but also inhibits vegetation growth on both sides of the finger, and thereby drives the instability. The time development of such an instability is illustrated in Figure 1 below."

The researchers further suggest possible local manipulations in the front zone that can trigger the instability, such as the introduction of a new plant species that changes the water-uptake rate, or periodic clearcutting to reduce the competition for water. Once the instability sets in, a gradual self-recovery process begins with no need for further intervention. “Other types of front instabilities can be envisaged that result in self-recovery, but additional studies, both theoretical and empirical, are needed to fully explore these ideas and their translations into land-management practices", says Prof. Meron.

Figure 1. Snapshots of model simulations showing reversal of desertification induced by a front instability. Green and yellow colors denote, respectively, vegetated and bare-soil areas. The snapshot times are in units of years.

Media Coverage:

Breaking Israel News

The Jewish Press