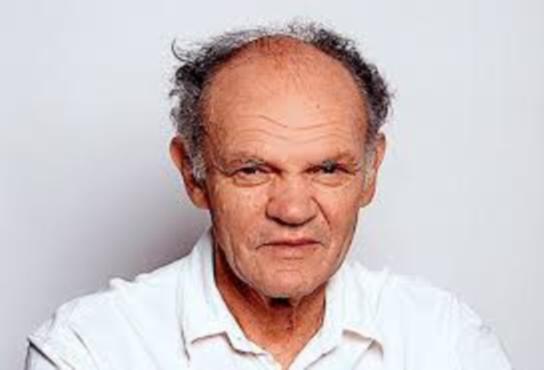

Photo Credit: Weizmann Institute of Science

Leslie Leiserowitz was born in Johannesburg in 1934. He obtained a B. Sc. in electrical engineering at the University of Cape Town (UCT), followed by an M. Sc. in X-ray crystallography.

Interview with Leslie Leiserowitz.pdf

Interview with Leslie Leiserowitz.pdf

Interview Excerpt

UD: Coming from South Africa, at the end of 1959 you joined the department of X-ray crystallography under Gerhard Schmidt at the Weizmann Institute. According to files at the Weizmann Institute archives, you spent just over a year a year, from late 1966 until early 1968, at the Dept. of Organic Chemistry of the University of Heidelberg, in order to help establish and run a new laboratory of X-ray crystallography for organic compounds. I would like to learn more about the crystallography department at the Weizmann Institute and its specific orientation. Was its approach similar to that at Oxford, where Gerhard Schmidt had studied?

LL: Our department, although titled the Dept. of X-ray crystallography, was primarily engaged in Solid State Chemistry. So that you can get a sense of what made the department so unique I would like to describe to you a little about the people who worked there from 1960-1965. The department was characterized by a hodgepodge of different languages. Gerhard Schmidt was fluent in German, English, and French. He also spoke Italian; which he probably learnt when he was in the Italian speaking sector of Switzerland after he left Germany with his mother. His Hebrew was not as perfect, but English was like a second mother tongue, probably because he attended a very good school in London and was still young enough to acquire an English accent. He told me that as a boy he had been involved in street fights with the Nazis. Strangely enough, in 1938, four years after he had left Germany, he received call up papers from the German Army; bureaucracy functioned. In the early stages of the War, he was sent, together with many others in England, as an enemy alien to a camp in Australia; the inmates were treated badly during the first few months after which things improved when Schmidt sent a letter to a Quaker woman describing the conditions under which the inmates lived.

Related Interviews: Jack Dunitz