Dunes are naturally formed mounds of loose sand built up by the wind. Unlike other kinds of soil that tend to congeal, the low cohesion nature of dry sand enables the fine particles to be swept up by the wind in a leap-like movement known as “saltation.” Because coarser sand particles can only be lifted by extremely powerful winds, they tend to be driven along the surface in a creeping motion, known as “reptation.” This heterogeneity of movement leads to a partition of particle size, with the finer sand building up preferentially in the upper levels of the dune.

Dune building is a complex process affected not only by particle size distribution, but by the wind regime (its direction, strength and frequency), geographic features and annual precipitation. Moreover, vegetation – when present – has major effects on the stability, movement, size and structure of the built-up sand. Therefore, classifying dunes is a complex task, leading to different ways of describing their attributes. Geologists, for example, will look at their distribution on the ground, referring to dunes as:

simple dunes, which exist as individual sand deposits, clearly separated in space from one another;

compound dunes, where two or more of the same kind of simple dune are coalesced or superimposed; and

- complex dunes, in which two or more types of simple dunes are intermingled.

Since dunes move and change shape, these too are useful descriptive factors. There are therefore:

migrating or active dunes, which move with little change in shape and dimensions under the influence of unidirectional winds;

elongating dunes, which elongate under the influence of winds hitting the dune obliquely from two directions and are characterized by little migration; and

- accumulating dunes, which exhibit no net advance or elongation, but increase in height and width.

There are also the influences of the physical lay of the land and local flora. Therefore, dunes are also grouped into those accumulating due to physical conditions on the ground, those forming in open, hyperarid desert regions with no vegetation, and those created in areas that can support vegetation.

Some of the most frequently studied dunes are described as:

Barchans – crescent-shaped, active dunes that develop under conditions of limited amounts of sand. Typically, barchans are simple dunes, separated from one another, that exist in a group. They are formed in the absence of vegetation and by a unidirectional wind regime. Because the wind climbing a barachan diverges somewhat from the crest towards the flanks, its speed is more rapid on the sides, causing them to advance more quickly than the crest and shaping it into a crescent-like structure.

Transverse – a variety of barchan that results from the coalescence of several barchans into a large dune. It is created when there is sufficient sand for formation of many close-lying barchans.

Parabolic – a U-shaped dune that forms in humid coastal areas, with vegetated arms. They take their shape from the vegetation that can preferentially grow at the base of the dune, close to the water table. Vegetation and wetness along the base retards sand motion of the less mobile arms under the force of wind power. The unprotected center of the dune thereby moves preferentially downwind, giving it the shape of a parabola with arms pointed upwind.

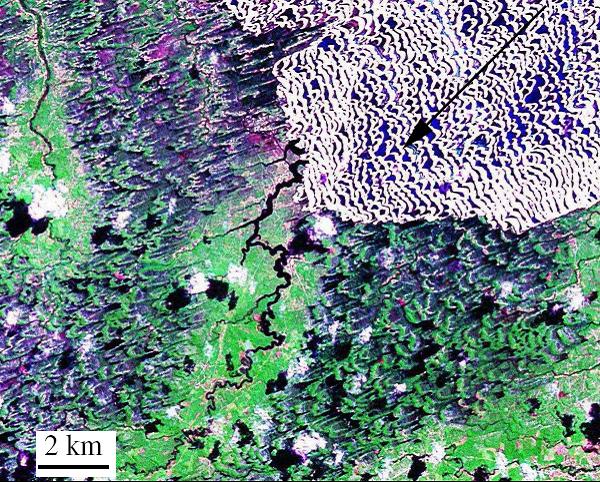

Lencois Maranhenses in northeastern Brazil (430W, 20S); a field of active barchan dunes (upper right corner) coexsist with fixed vegetated parabolic dunes. The average annual precipitation is 2400 mm/y and the DP is over 1000. In spite of the extremely high rainfall, many dunes are active due to the strong winds.

Linear or seif – the most common inland dune, which can be vegetated or unvegetated and forms in a bimodal wind regime. When winds generally blow from two primary directions, say from the north and the east, sand advances on the average towards the southwest, forming a long, narrow, linear dune that points in that direction. Because of the north and east winds, the sand is piled up with steep crests caused by slip-faces on both sides. When vegetated, the dune is low, with rounded profiles. This results from plant stabilization of the sand, which modifies the slip-faces.

Linear vegetated dunes at the western Negev Israel. Aeoilan activity is restricted to the dune crest where as the flanks are fixed by biogenic crust and vegetation.

Star – a star-shaped dune with multiple slip-faces that forms when winds come from multiple directions. These accumulate sand, but do not migrate.

Reversing – a dune with a straight, linear shape with a triangular cross section that forms when the wind regime is bidirectional in opposite directions.

Echo – a dune formed when unidirectional wind flow blows sand towards the bottom of a rising cliff, a common geological formation near a shore. Because of a helicoidal vortex of air flowing parallel to the cliff, a sand-free area is formed between the dune and the cliff.

Foredunes – vegetated sand ridges on sandy backshores where vegetation can grow and trap aeolian sand. These dunes prevent the movement of beach sand into the land’s interior.