"We want to transform the definition of autism

from one that is behavioral to one that is biological”

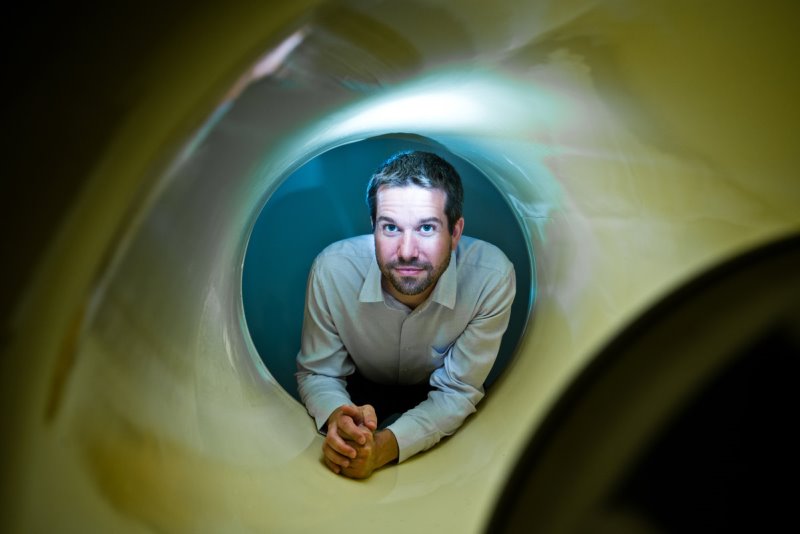

Dr. Ilan Dinstein

Currently, one in every 100 children in the US is diagnosed with autism, with similar numbers in Israel. These figures have skyrocketed since the 1980s, when only one in five thousand received this diagnosis. Autism is hence rapidly becoming the most prevalent developmental disorder in children worldwide.

The diagnosis is based entirely on behavioral criteria, which include the existence of social difficulties and communication deficits. The disorder is often identified at the age of 2 or 3 in places where awareness is high, but may also easily remain undiagnosed or misdiagnosed for many years. At present, there are no objective biological measures that can aid clinicians in identifying autism.

To this end, Dr. Ilan Dinstein from the Department of Psychology and the Zlotowski Center for Neuroscience is establishing Israel’s first neurophysiological autism lab at BGU.

While other labs in Israel that investigate autism study behavior, Dinstein focuses on the brain. “We want to transform the definition of autism from one that is behavioral to one that is biological,” says the 37-year-old neuroscientist, who was drawn to the field of autism for two main reasons: the desire to work on a clinically relevant topic and the personal experience of having a cousin with autism.

“During the last ten years or so, scientists have realized that autism is not one disorder, but rather an entire family of disorders with distinct biology. For example, there are many genes that raise the risk of developing autism, suggesting that there are multiple biological paths that may lead a child to display social and communication problems. In order to deal with autism more successfully, we must, therefore, characterize the different biological pathways that children with autism display,” he explains.

Dinstein seeks to reveal abnormalities in brain function and structure that are unique to young children with autism. His focus on early development – ages two to three, when the first symptoms are initially identified – is critical for his aim to develop novel diagnostic methods that will rely on objective biological measurements instead of subjective behavioral impressions.

To reach more accurate diagnoses, Dinstein and his team utilize neuroimaging tools such as MRI and EEG, as well as genetic screening and behavioral assessments. “We want to identify specific types of autism as early and as reliably as possible,” he continues. “If we can develop a tool that will reliably identify even 20-30 percent of autistic children based on MRI scans and/or EEG exams at the age of one, we will have revolutionized the field.”

In this effort, the advantages of early diagnosis of autism cannot be overstated.

“Even today, early diagnosis paves the way for early behavioral intervention, which leads to better prognosis. If we can understand what’s different in the biology of children with autism, we may be able to identify the mechanisms that need to be corrected,” says Dinstein.

“Rather than treating all individuals with autism using the same behavioral therapy, as we do today, it may be possible to develop targeted pharmacological therapies that will nudge the child’s development back to a typical course. The human brain has great plasticity during early childhood, which disappears as the brain matures and becomes more rigid. With developmental disorders, it is probably critical to intervene before this period of plasticity ends,” he explains.

Dinstein earned his PhD in Neuroscience at New York University, and did post-doctoral work at Carnegie Mellon University. At BGU he plans to continue his successful collaborations with autism experts around the world, who include Prof. Marlene Behrmann at Carnegie Mellon University and Prof. Eric Courchesne at the University of California at San Diego.

BGU provides an ideal setting for this type of research, according to Dinstein.

“We’re next door to the only hospital in the Negev, the Soroka University Medical Center, which serves a population of over one million people. Soroka has fantastic doctors,” he adds, noting that he has started working closely with the hospital’s pediatric neurologists and psychiatrists. The American Associates, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev raised funds from donors to purchase a new 3T Phillips

MRI scanner, which is mutually operated with Soroka and dedicated to research 50 percent of the time.

Working in the Negev also provides access to unique patient populations that may shed new light on the genetics of autism. Specifically, the local Bedouin community is faced with unique genetic issues due to widespread interfamily marriages and may, therefore, reveal important clues about how specific genetic abnormalities affect brain development in autism. In addition, says Dinstein, “The Negev population doesn’t move around much so we will be able to do longitudinal studies and follow-ups more easily.”

“Conducting this research in Beer-Sheva will also improve the treatment patients will get,” he says. “Kids in the Negev don’t usually receive EEGs and MRI scans as part of their diagnosis. The research will also enable a more thorough clinical characterization of participating children and give families detailed information about their child’s health.”

Coming to Beer-Sheva also represents something of a homecoming, as his father, Its’hak, is a professor emeritus of the Department of Electrical Engineering. Ilan Dinstein joined the BGU faculty in October 2012, choosing it over options in the USA – and in Israel – due to his connections with academicians and doctors here.

While he enjoyed his time in the States, Dinstein defines himself as “very Israeli.” In the military he served in an intelligence unit, and his closest friends remain Israeli. Despite his perfect American-accented English, he says he reserves English mostly for scientific use. Hebrew is for daily life.

“Being in Israel, at BGU, is part of my personal agenda,” Dinstein says. “I feel a deep motivation to develop the infrastructure that will enable us to perform top notch research about developmental disorders here in the Negev. I’m confident that we can do ground-breaking research here and there’s nowhere else I’d rather be.”

In recognition of his outstanding achievements, Dinstein was awarded an Alon Fellowship from the Israeli Council for Higher Education and the Sieratzki Prize for Advances in Neuroscience during his first year as a faculty member at BGU.